University Homes

Resurrecting the Ghosts of Those Who Lived Here Before Us

University Homes is a subdivision consisting of 83 row homes on Cloverhill and Canterbury roads located in North Baltimore just beyond the Johns Hopkins undergraduate campus, in the Tuscany-Canterbury neighborhood.

University Homes was built by the architect and George R. Morris, who had moved to Baltimore after the Great Fire of 1904 to assist in the city’s reconstruction. Morris had built multiple residences and apartment buildings prior to developing the University Homes neighborhood. Morris had the concept of building a neighborhood that could provide all the modern conveniences of an apartment complex, to attract an upwardly mobile young professional market that wanted the ease of aparatment living, but were desirous of home ownership.

University Homes Construction

Starting in 1914, Johns Hopkins University had begun moving its campus from its downtown location to its new Homewood campus, a process that was complete by 1916. By then, the nearby Guilford neighborhood built by the Roland Park Company was already well established, and little land was available for development. In 1917; however, Morris, was able to cut deals with the owners of the various large estates that were located along Charles Street (just beyond the new Hopkins campus). He purchased the back lots of their properties for his University Homes concept. The first units were completed by the end of that year; however, construction was slowed by the market conditions created during World War I, and the project would continue into the 1920s. Photographic evidence shows that the neighborhood was completed circa 1921; however, sales of units continued for an additional 5 years.

Promotion - Making University Homes Possibly the

Most Famous Housing Development in America in the 1920s!

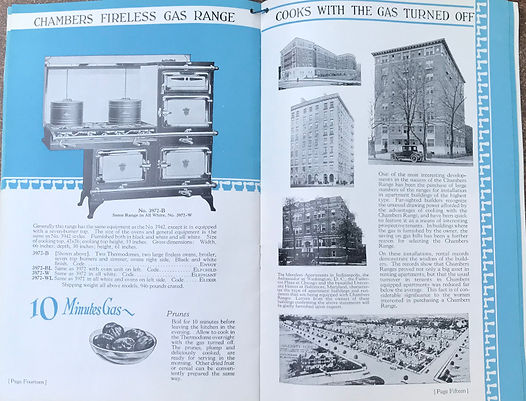

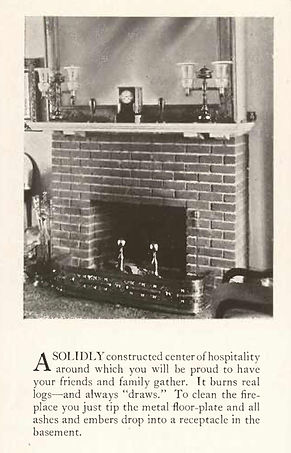

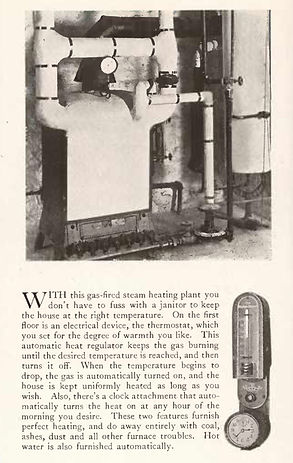

Morris’ ideas for both the construction and promotion of University Homes were truly innovative for their time. All the homes were built with gas heating and equipped with set-it-and-forget-it thermostats and Chambers gas stoves. It was the first such all-gas community built in the United States! Previously heating was supplied by coal and basements were dirty and uninhabitable.

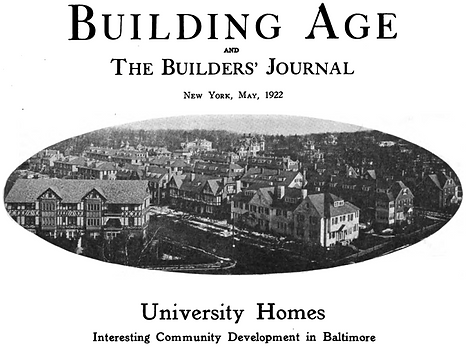

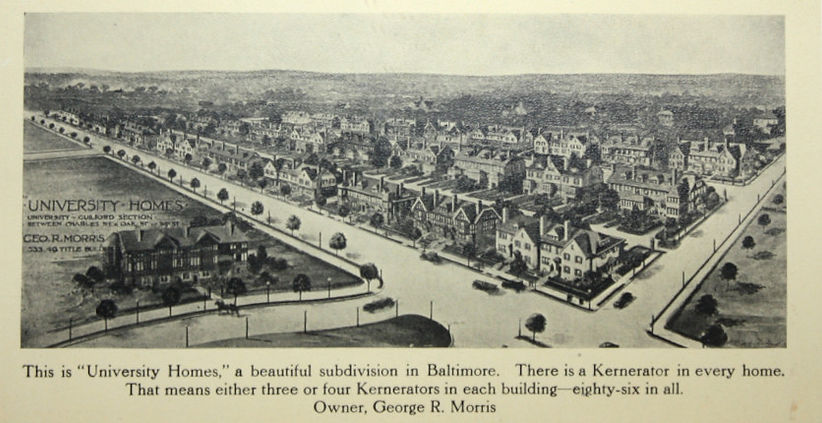

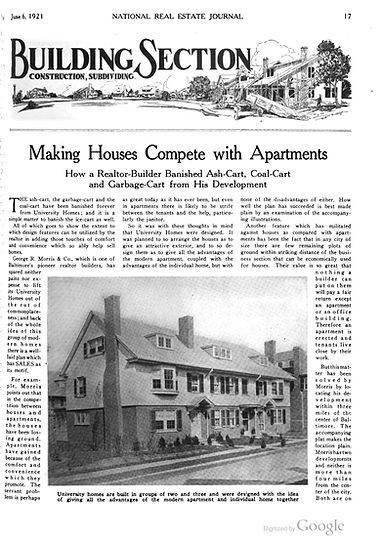

The innovation was such a big deal that an artist rendering of what the neighborhood would look like when complete was created for Consolidated Gas and Electric (later BG&E) magazine. That image would go on to be featured in multiple journals and magazines.

Above: The BG&E image of the neighborhood as it re-surfaced in the Chambers Gas Stove product catalogue.

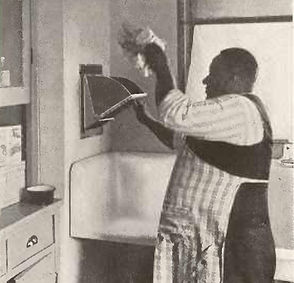

To Left: Every University Homes house came equiped with a Chambers gas stove. This image comes from the neighborhood sales brochure!

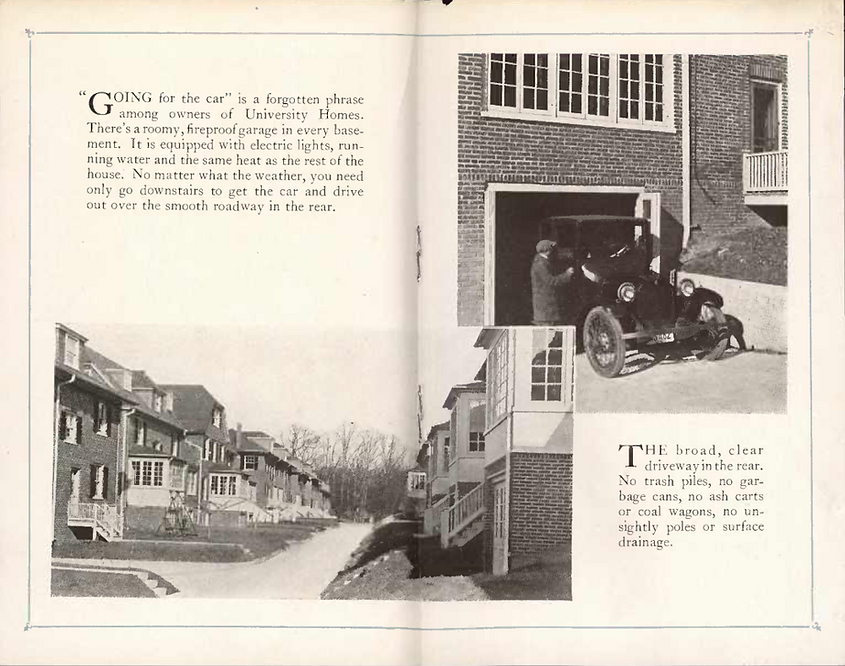

All homes had built-in and fireproofed (and steam heated!) car garages, at a time when the popularity of automobiles was just taking off. All units also featured a Kernerator garbage incinerator in the basement and a garbage chute in the kitchen, so that trash could be disposed of easily. Homes were sold with the option of an electric refrigerator, and electrical service was buried to improve the quality of the living space around the home. The units were designed and marketed to a more well to-do segment of the population. A large walk-in cedar closet was included to protect important garments from insects. The top floor was generally designed as servants quarters and an electrical call system was included with foot triggers located under dining room tables so that the help could be easily alerted.

Left: University Homes featured in Kernerator incinerator advertisement.

Below: Image of the incinerator system as featured in the sales brochure.

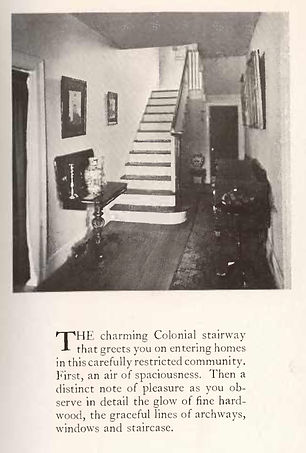

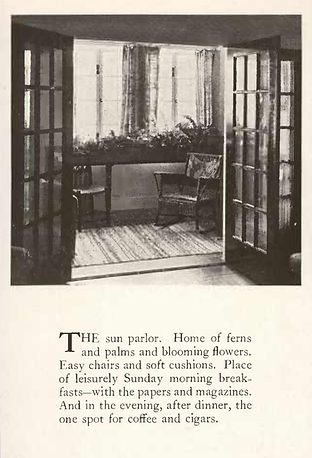

The proliferation of images of the University Homes development across the county was no fluke occurrence. George Morris was a consummate marketer and came up with novel ways to promote the neighborhood. It started with a 13 page brochure which included high quality photos of the homes and detailed explanations of the features and benefits.

These brochures and photos then served as the basis of materials that were sent to national journals and magazines to promote the development. Multiple organizations picked up the story, with the National Real Estate Review and Builders Age Magainze each producing two articles on University Homes, published in separate issues. The first of the articles highlighted the homes' construction, conveniences and novelty and the second discussed how the development's marketing strategy.

In all these articles, Morris pushed the idea that his development would make life cleaner and easier as "the ash-cart, the garbage-cart and the coal-cart have been banished forever from University Homes."

In what was truly a first-of-its-kind promotion, Morris worked with Baltimore retailers and manufacturers to completely outfit a model home in the neighborhood with more than $52,000 of goods (nearly 1 million in today’s dollars) A booklet entitled “The Ideally Furnished Home” was created that was given to visitors that toured the homes. The brochure included detailed explanation of the goods on display and where they could be purchased. The event was an unmitigated success, with more than 27,500 people visiting the model home! In what felt like a minor miracle, self-appointed neighborhood historian Joshua Cohen was able to track down Jo-Anne Smith, George Morris’ granddaughter, who now lives in Pennsylvania. She was holding onto what is most likely the only existing copy of the “Ideally Furnished Home” and was so gracious as to get copies made for the neighborhood’s centennial project.

The event was an unmitigated success, with more than 27,500 people visiting the model home!

Above: The Ideally Furnished Home promotion as featured in Builders Age magazine

The First Families of University Homes

While it is fascinating to contemplate how George Morris turned University Homes into one of the most widely known concept communities in the United States, of course, neighborhoods are much more about people than they are about architecture and conveniences.

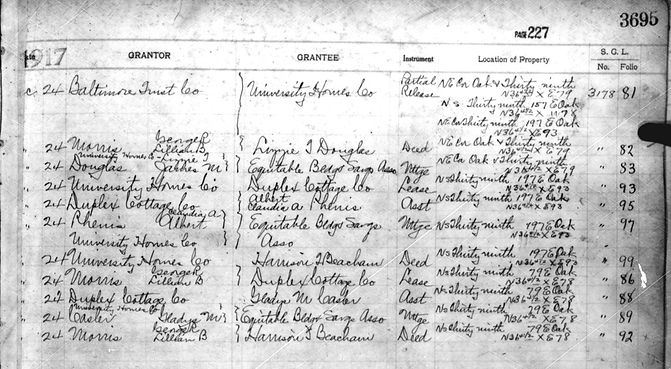

As the centennial approached, neighbor Joshua Cohen decided he wanted to know something about the first folks that lived in the neighborhood. Utilizing online real estate records and block books, Cohen was able to trace the home deeds to reveal the names of first homeowners.

Utilizing digitized Baltimore Sun papers, Ancestry.com and other online resources, Cohen was able to then create family trees of all 83 first families of University Homes! In some cases, he was able to contact surviving descendants to get additional information, photos and anecdotes about the first families.

The Creightons

Little by little all the first families were revealed to be real Baltimoreans that had full and fascinating lives!

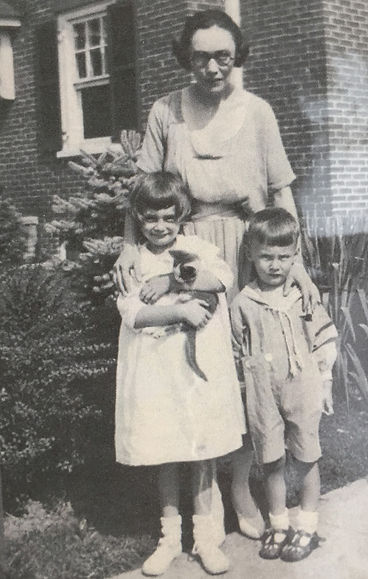

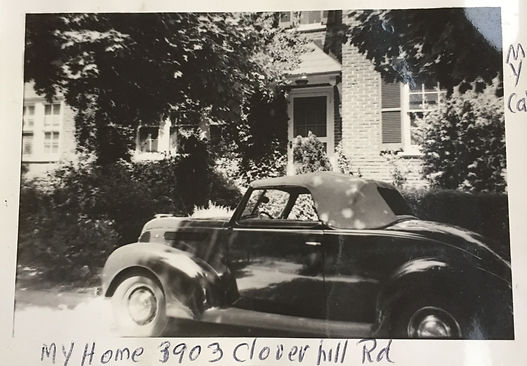

For example, 3903 Cloverhill was purchased October 16, 1918 by George W. Creighton (b. 3/22/1890, d. 9/1/1984) and his wife Margaret Patton Wilson (b. 1/28/1889, d. 9/23/1963). They brought up two children there: Margaret Creighton (b. 6/11/1915, d. 3/17/1993) and George W. Creighton III (b. 6/22/1918,

d. 7/27/2008).

George Creighton came to Baltimore in 1918 as an assistant general superintendent of the Hess Steel company. He worked in various industrial jobs and by the end of the 1920s he became then the VP of the Industrial Corporation of Baltimore — consulting with corporate heads about engineering problems and plant operation analysis. During WWII, he became the Maryland Manager of the War Production Board helping coordinate the economy’s transition from civilian to war production.

After the war, he worked for the Baltimore Chamber of Commerce. He was an elder at the Second Presbyterian Church. Margaret Patton Wilson was a native of Indiana PA, active in the Second Presbyterian church and a president of its women’s association. She died at the Cloverhill home in 1963.

Malcolm, Ritta, and Elizabeth Douglas

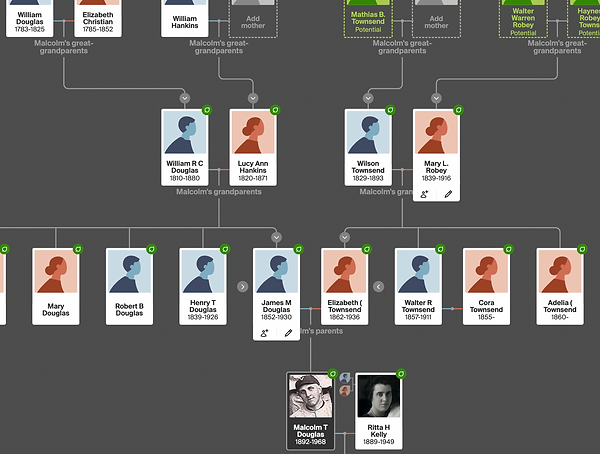

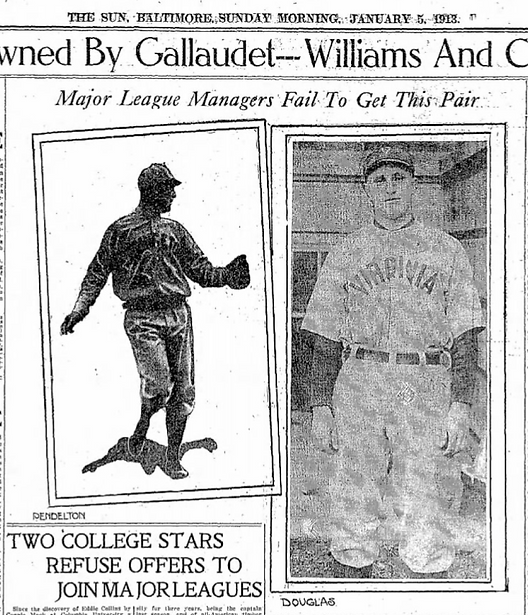

Another example of the rich family history that was revealed by Cohen’s genealogical work was the story of the first homeowners of his house at 3914 Cloverhill Road. It was purchased April 1, 1919 by Malcolm Townsend Douglas (b. 7/13/1892, d. 4/24/1968) and his wife Ritta Hammond Kelly (b. 11/5/1889, d. 3/8/1949). They brought up their daughter Elizabeth Douglas (b. 1918, d. 2011) at the home.

Malcolm went to the University of Virginia where he studied law. While there, Malcolm became an accomplished Shortstop for the University baseball team. Upon graduation multiple baseball teams made offers to get him to join the majors, including the New York Giants and the Baltimore Orioles!

Ultimately, Malcolm decided to forego baseball and join his father’s real estate business. James Malcolm Douglas was another University Homes first family, purchasing 6 W. 39th Street with his wife Elizabeth F. Townsend. The family had a big footprint at University Homes, as Ritta’s sister, Lillian I. Kelly was also in the neighborhood, purchasing 3943 Canterbury along with her husband Stephen Lee George!

Sadly, the marriage went south during the great depression and Malcom and Ritta eventually divorced.

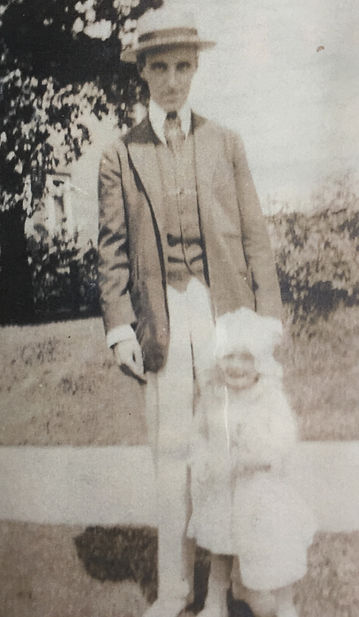

Malcolm and Ritta’s daughter Elizabeth had a long and happy life. She had two sons, Michael and Patrick Miller. Patrick still lives in the Baltimore area and came to a TCNA meeting where we discussed the history of the first families. He was welcomed as a celebrity!

Elizabeth can be seen here at the age of 92.

There is not enough space here to discuss the histories of all 83 first families. However, behind every home are truly fascinating, heart-warming and at time tragic stories of the real people that lived in these homes before us. We are all part of the flow of human history and the American experience.

Below you can see the list of the first homeowners of our beloved University Homes. If you are curious about getting to know any of them with a bit more detail, your neighbor Joshua Cohen can help you uncover their stories.